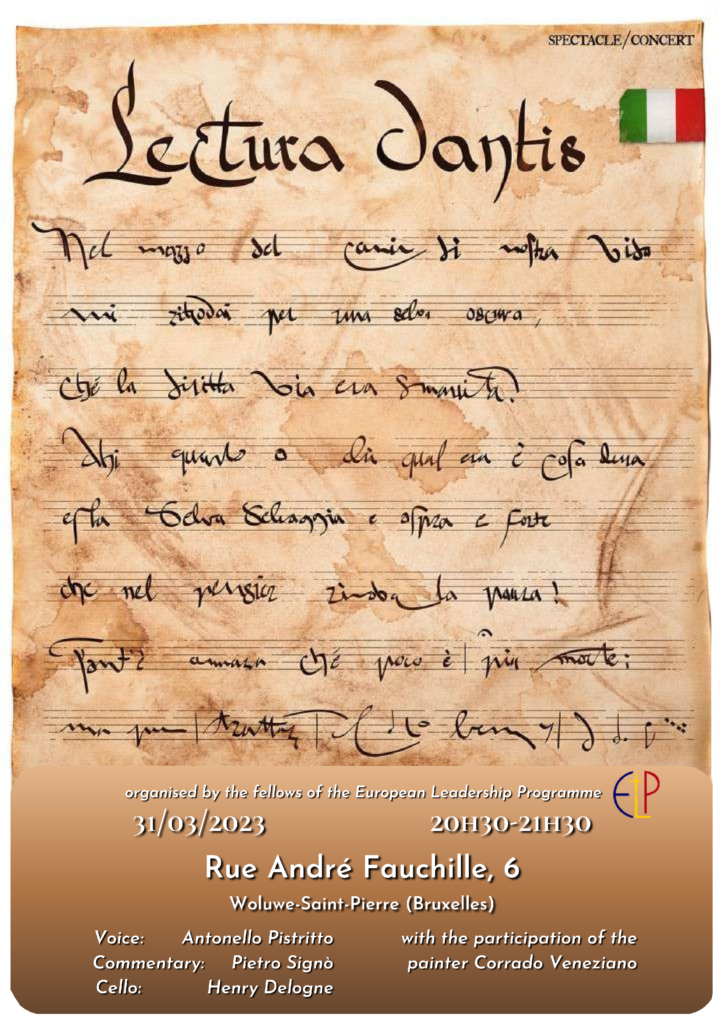

Saturday 25th March was celebrated all over the world the “Dantedì,” a day of commemoration of the Italian poet Dante Alighieri, writer of the “Divine Comedy.” To celebrate him, the ELP fellows organized on 31st of March a Lectura Dantis. During the event they shared a musical experience as a concert in which the voice (Antonello Pistritto, ELP fellow) and the cello (Henry Delogne, Belgian lawyer and celloist) were the main stars. This was followed by a commentary in English from Pietro Signò, current ELP fellow. The event had the participation of Italian painter, Corrado Veneziano, who was host at the Committee of Regions for exhibition “Erasmarrita. Dante, Europe and other heavens.”

Reading Dante out loud is an ancient “ritual” that finds its roots a few years after the writing of The Divine Comedy, which was completed in 1321. For those not familiar with it, it is a book that tells the story of the spiritual journey of the author, Dante, through the otherworldly worlds of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. The reason ‘The Comedy’ is still worth reading today lies in the fact that it is a journey of personal awareness through powerfully evocative images. We can learn the meaning of Dante’s work through his own words in the following lines of a letter he wrote to Can grande alla Scala:

“[I]t must be known that the sense of this work is not unique, indeed it may be said to be polysemic, which means with several senses; for the first sense is that which is obtained from the letter, the other is that which is obtained from the things signified through the le+er. And the first sense is called literal, the second allegorical, or moral, or anagogical. And although these spiritual senses are called by various names, they may all generally be called “allegorical,” being different from the literal or historical. For allegory is said from the Greek alleon, which in LaPn is called a lienum or diversum. […][I]t is manifest that two must be the subject: […] taken only in a literal sense, the state of souls a6er death […]; […] taken the work allegorically, the subject is man, inasmuch as deserving and demeriting by way of free agency he is subject to the justice of reward and punishment.”

Several centuries after, French Cardinal Henri De Lubac, a Jesuit, wrote a four-volume analysis in the 1950s on medieval exegesis and the 4 senses of Scripture, taking up what was crystal clear to Dante.

But why talk about this today? Because the interpretative approach is the key to accessing the real meaning of any kind of text. This is most evident in the biblical or poetic text, but it also applies to the legal text, foundational to society, and which aims, through compliance with formal rules, to achieve universal values such as peace and justice.

Precisely because these values are universally understandable – as much as the emotions that move the human soul such as pity and love – Dante writes ‘The Comedy’ in a language that speaks not only to minds, but also to hearts. The musicality of the text, the rhymes, allows its comprehension regardless of the understanding of the Italian language. And tonight, this is even more possible thanks to the combination of words and music thanks to the presence of Henry Delogne, who with the sound of his cello will duet with my voice in a real concert.

The three proposed passages were:

– Inferno V: tells of the entrance into Hell, the judgment of souls operated by the guardian and judge Minos, the ceaseless storm of the souls sinful of lust, and the encounter with Paolo and Francesca, lovers and condemned because they were discovered in flagrante by her husband and his brother. The love story is sweet and sad. Dante feels pity because Love is God’s own feeling and it is what drives human beings to perform all actions, good or bad;

– Inferno XXVI: tells of Ulysses who is depicted as a speaking flame. Dante’s Ulysses instead of staying in Ithaca after his return, decides to take to the sea again to set out on an adventure, to become “expert in the vices and virtues of men.” Taken by this desire for the infinite, he goes to the ends of the earth. In hell between the fraudulent counselors, not so much for his hubris, as for inciting his companions to follow him against the limits of the human nature;

– Paradiso XXXIII: After passing through hell, purgatory and heaven, Dante is finally at the end of his journey. He is about to contemplate God. He can’t describe him, but in a burst of mystical ecstasy he tries to describe him as a great point of light that unites together all philosophy and theology theories. With evocative images, he describes both mystery of trinity and incarnation. Then his mind is blinded by too much knowledge and light emanating from God, who – in his loving motion toward creation and creatures (according to the Aristotelian conception of astronomy) – moves the sun and stars.