For those who wish to accompany the current climate emergency, it is always helpful to have a scientific-based approach to the topic. One good way of doing so is to keep up-to-date with the latest reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). IPCC is a scientific body, created by the United Nations (UN) in 1988, made of thousands of experts who are tasked with periodically summarising the best scientific knowledge on climate change.

The most recent report from the IPCC was the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), published in March 2023. The report summarises the latest knowledge and recommends steps on mitigating and adapting to climate change, as well as brings together the best scientific research from the past four years.

With many important takeaways from the report to bear in mind, here is our choice of five, which relate to JESC’s mission of social-environmental justice.

- International cooperation is essential

The most important revelation to be found in this report is the reaffirmation that global warming is human caused and that net zero CO2 emissions must be achieved.

The report states that “cumulative carbon emissions until the time of reaching net zero CO2 emissions and the level of greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions this decade largely determine whether global warming can be limited to 1.5°C or 2°C.” In other words, global warming is determined by the total amount of GHG emitted throughout history. The more emissions we have, the higher the temperatures will go. The only way to stop global warming is to eliminate GHG emissions entirely. This means that not only should we not let new investments happen into fossil infrastructure, but also that some of the existing GHG producing industrial facilities should be eliminated before the end of their lifecycle, in a hard economic decision that scientists deem essential to stay below the 1.5°C warming threshold.

The document confirms that we have ten years to take control of the climate emergency and make real progress on net zero. Considering this, the IPCC reminds us of the importance of intergovernmental cooperation by commenting that “there is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”

In light of the upcoming COP28 conference in Dubai this Fall, the report states that “climate resilient development integrates adaptation and mitigation to advance sustainable development for all, and is enabled by increased international cooperation.” The Conference of Parties (COP) process allows for coordination and vision in building a peaceful solution to this crisis, therefore it is important that radical progress is made at these meetings.

2. The poorest are the most vulnerable

The report also reveals the shocking reality that “approximately 3.3 to 3.6 billion people live in contexts that are highly vulnerable to climate change,” with the poorest countries suffering the most. “Between 2010 and 2020, human mortality from floods, droughts and storms was 15 times higher in highly vulnerable regions, compared to regions with very low vulnerability.” Under realistic climate scenarios, 1 billion or more humans would be forced to leave their homes as their regions would become physically uninhabitable. Most of these places are in the tropical regions across all continents.

This fact was already addressed by Pope Francis, who wrote in Laudato Si’ that the cry of the earth is also the cry of the poor. “Regions and people with considerable development constraints have high vulnerability to climatic hazards” and this has “exposed millions of people to acute food insecurity and reduced water security.” Geographically, this affects “communities in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, LDCs (Least Developed Countries), Small Islands and the Arctic, and globally Indigenous Peoples” the most.

3. There is plenty of opportunity for climate justice

A significant theme of the report is the historic inequality which exists in this current crisis. “Historical contributions of CO2 emissions vary substantially across regions in terms of total magnitude,” the report states.

The report claims that 10% of households with the highest per capita emissions contribute 34–45% of global greenhouse gases compared to the bottom 50% which contribute 13–15%. Thus, an interesting take-away from the report is its emphasis on stating that “prioritising equity, climate justice, social justice, inclusion, and just transition processes can enable adaptation and ambitious mitigation actions and climate resilient development.”

Justice is particularly important when considering, for instance, that wind turbines are estimated to require up to 14 times more iron needed than fossil fuel power generation, and that the supply of cobalt, which is needed for batteries, will need to increase by 500% in the lead up to 2050. These resources are found in the poorest countries in the world, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, so it is important that this transition is not only ‘green’ but also ‘just.’ The report sets out the opportunities and challenges that this transition presents. “Adaptation outcomes are enhanced by increased support to regions and people with the highest vulnerability to climatic hazards. Integrating climate adaptation into social protection programs improves resilience.” In other words, the consequences of the climate crisis are clear, but what this report advocates for is a route to climate justice.

4. Food systems are important

Food systems are high emitters of greenhouse gases. In the EU, agriculture is the third largest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, the EU spends €38.2 billion on subsidies to the agricultural sector (Common Agricultural Policy). Thus, agriculture and food policy are very important in addressing the climate crisis, which this IPCC report confirms.

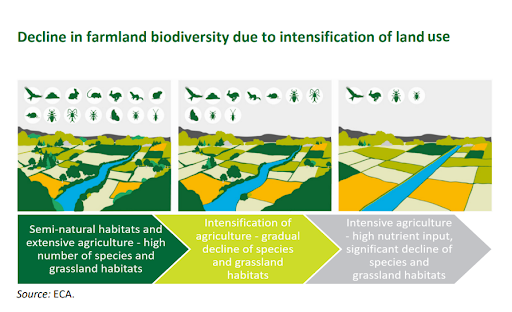

It suggests that it is equally important for individuals to change their habits through “demand-side measures… shifting to sustainable healthy diets and reducing food loss/waste.” As for policy makers, it’s important to ensure that “sustainable agricultural intensification reduces ecosystem conversion and methane and nitrous oxide emissions, and free up land for reforestation and ecosystem restoration.” In practice this requires drastic changes in our farming techniques, the chemicals we use, the crops we rely on. It also means that much less meat should be produced and consumed.

The authors of the report point towards reducing the carbon footprint of global agriculture through “cultivar improvements, agroforestry, community-based adaptation, farm and landscape diversification, and urban agriculture.” These are all technologies and techniques used to increase the biodiversity of the land we use, as a way of accommodating nature, stabilising the water-cycle and capturing carbon. These measures not only mitigate climate change, but also adapt to what is already inevitable.

Importantly, the report equally argues for the need to increase biodiversity in general. It suggests that rebuilding overexploited ecosystems “reduces negative climate change impacts on fisheries and supports food security, biodiversity, human health and well-being.” Especially considering the huge impact which food systems have on EU policy, this is a theme which requires all of our attention.

5. A reminder of our impact on future generations

Finally, another striking observation made in the report is the impact of our actions today on the future population. There is the potential that a child born in 2020 could witness excruciating temperatures as they grow up.

In a worst case scenario, a person born in 1980, can expect 2ºC warming by the time they reach 70 in 2050. By this point and preferably before, temperatures must start to fall, but if they do not, then the consequences for a child born in 2020 will be severe. A three year old today, who will be aged 70 in 2090 could see 4°C warming. This would involve almost sauna-like indoor temperatures for most. On the other hand, if we act efficiently today, the same toddler, as she grows old, would see declining temperatures by the end of her life. Here again, we see that it is the poorest nations which would suffer the most. For example, according to the World Food Programme, the food insecurity of Bangladesh could increase by 88% in comparison to the present day if temperatures reached 4°C warming.

The report details how since 1961, crop productivity in Africa has shrunk by a third and that since 2008, extreme floods have displaced 20 million people a year. These threats increase with every rise in temperature. Moreover, the changes which lead to this will be “irreversible on centennial to millennial time scales” and will only “become larger with increasing global warming.”

Conclusion

The revelations in this synthesis report are at least alarming, but two powerful elements can be singled out. Firstly is the fact that children born today might have to live in a world of incredible heat because of the likelihood of 4ºC warming. This fact is accompanied by the warning that the rapidly closing window of opportunity to limit global warming to 1,5-2°C has narrowed down to the next ten years. So we have ten years to make net zero emissions happen. This is a remarkable statement.

The report concludes that “without urgent, effective, and equitable mitigation and adaptation actions, climate change increasingly threatens ecosystems, biodiversity, and the livelihoods, health and wellbeing of current and future generations.”

Annex: JESC work on Ecology

Despite how seemingly overwhelming the task might be, it is equally important to acknowledge the response of many states, intergovernmental bodies and civil society’s institutions. JESC Ecology adds its “two cents” of work to this collective effort, and invites everyone to keep in touch:

- The JESC Carbon Initiative (JCI) has been working together with religious communities, institutions and schools to develop carbon inventories and design paths towards reduced carbon emissions and, ultimately, climate neutrality. More can be found here.

- The Future Generations Representative (FGR) project is an ambitious venture which goes to the heart of this IPCC report by ensuring protection for future custodians of the world. Read more here.

- JESC started recently to work on the sustainability of food systems, and to accompany the important pieces of EU legislation that are in the making. There’s great interest in knowing other faith-based organisations working on the topic, and the invitation can be read here.

- Finally, together with partners plans are being made to closely follow the upcoming COP28, with some preparatory activities of awareness raising and advocacy. Keeping up to date with this work can be achieved by means of the JESC Ecology newsletter Eco-Bites, that can be signed here.