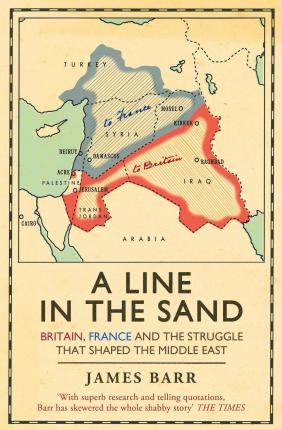

“A Line in the Sand”: Britain, France and the Struggle that Shaped the Middle East by James Barr

Through the European Leadership Programme, every cohort of fellows engages in the long-standing Jesuit tradition of forming leaders to change the world. It is clear, even to the most casual reader of A Line in the Sand by James Barr, that neither the British diplomat Mark Sykes nor the French diplomat François Georges-Picot received any such leadership training.

Indeed, their short-sighted attempt in 1916 to divide the Middle East between their two countries—in an agreement known to history as the Sykes-Picot Agreement—not only condemned the Middle East to a century of upheaval but also provides an enduring case study for how leaders should take care not to behave. Nonetheless, complex historical events do not always boil down to the decisions of one or two men, and this book introduces its reader to the cast of characters whose private ambitions, resentments, and sympathies created the political environment in which the Sykes-Picot Agreement could assume its abiding importance.

Barr weaves his historical narrative out of the rich strands of the ancient Franco-British rivalry. As the author acknowledges in his prologue, the inspiration for A Line in the Sand originates in the discovery of newly declassified materials about a Franco-British proxy war in the Middle East during the Second World War. The documents reveal that the antagonism between France and the British Empire played out in the Middle East during both World Wars despite France and Britain’s alliance therein. As Barr summarizes the situation in 1945, “while the British were fighting and dying to liberate France, their supposed allies the French were secretly backing Jewish efforts to kill British soldiers and officials in Palestine” (1). From there, Barr’s historical account examines how the French and British arrived to such a point despite their decades-long efforts to avoid conflict in the Middle East by dividing the region between themselves. The unfolding circumstances presented in the first part of the book beg the question: if the two powers had concluded an agreement in 1916 to stay out of each other’s way, how is it that they fought a proxy war well into the 1940s?

The documents reveal that the antagonism between France and the British Empire played out in the Middle East during both World Wars despite France and Britain’s alliance therein. As Barr summarizes the situation in 1945, “while the British were fighting and dying to liberate France, their supposed allies the French were secretly backing Jewish efforts to kill British soldiers and officials in Palestine” (1). From there, Barr’s historical account examines how the French and British arrived to such a point despite their decades-long efforts to avoid conflict in the Middle East by dividing the region between themselves. The unfolding circumstances presented in the first part of the book beg the question: if the two powers had concluded an agreement in 1916 to stay out of each other’s way, how is it that they fought a proxy war well into the 1940s?

The answer lies in the procession of historical figures, both high and low level, from Winston Churchill to Faisal I of Iraq, that Barr marches across his book’s pages. A Line in the Sand is the story of how dozens of figures—lawyers and diplomats and archaeologists and Bedouin assassins—whose legacies languish in the shadows of Messrs. Sykes and Picot made individual decisions of varying importance that together caused the forces of imperialism, Zionism, and Arab nationalism to collide in Palestine and reverberate ever since. American history textbooks, such as those I had to read in high school and college, tend to present the Sykes-Picot Agreement as something between an exercise in bureaucratic negotiation and a formal treaty.

James Barr, however, uses plentiful documentary evidence to show how the agreement “had been an academic exercise to resolve an argument, not a blueprint for the future government of the region” (36). Moreover, Barr says of the agreement that although “a hypothetical division of country that neither of its signatories yet controlled, it was extremely vulnerable to events, all the more so because it was a secret that was bound to cause controversy when finally it was exposed” (36). In many ways, the agreement continues to shape the events of the present. Any student of leadership would thus benefit from studying how decisions can outgrow their makers and take on lives of their own.

One unexpected strength of this book is its presentation of France and Britain’s intrigues in the Levant over a few decades as key to understanding European politics over almost all of the twentieth century. The drama around Sykes-Picot made celebrities out of little-known persons, as in the case of T.E. Lawrence, shaped the political philosophies of rising stars, such as Charles de Gaulle, and supercharged the public personae of people already in the spotlight, Winston Churchill chief among them. More than that, James Barr lays out a chain of events that lead from the Ottoman Empire’s entry into the First World War to the Arab Revolts to the fall of Vichy France to the UN’s approval of its Partition Plan for Palestine, with the Sykes-Picot Agreement in the middle of it all.

If that does not suffice to speak to the book’s wisdom, Barr’s epilogue might even ring prophetic for students of modern European politics. Eleven years after the 1947 UN vote to split British Mandate Palestine into two ethnic states, the United Kingdom attempted to enter into another agreement, this one signed in Rome. Though its drive to join the European Economic Community (ECC) did not much resemble its scramble for colonial possessions, the United Kingdom failed to secure the support it needed to join what would later become the European Union. That lack of support hinged on the experiences of one man who had experienced the aftermath of the Sykes-Picot Agreement as a young officer in the Middle East. In Barr’s telling, “the general’s [Charles de Gaulle] experience of British machinations in both places [Beirut and Damascus] profoundly shaped his reluctance to allow his wartime rivals to join his European club” (377) and so he vetoed the UK’s accession to the EEC.

In order to figure out if the Sykes-Picot Agreement precipitated not only the destabilization of the Middle East but also Brexit, one has to read A Line in the Sand. It is the rare book that can inform and entertain Francophiles and Anglophiles alike. The tale of Sykes-Picot is essential for understanding the modern world and learning leadership principles in the process. It is also an interesting investigation into the French and British characters. However, as Barr himself warns, “It is a tale from which neither country emerges with much credit” (377).

Anthony J. Tokarz

5th Cohort Fellow